Chances are that preparation for emergencies is part of your tour planning (if not, it definitely should be). And chances are, your route has sections without cell phone coverage, so you start thinking about:

- Points of no return

- Possibilities for emergency shelters

- Easiest ways to hike out if you have to abort the tour

- Emergency kit in case of injuries

But what do you if everything fails and you encounter a life-threatening situation? How do you call the rescue services in the backcountry without cell phone service?

Disclaimer: This is not a product review. We will look into different methods and type of emergency communication devices you could use to call the mountain rescue service. However - spoiler alert - at the end of the article, I will tell you that I own a Garmin inReach Mini and that I'd definitely recommend it.

But first, let's have a look at the options you have without using any communication gadgets.

Signal for help without an electronic communication device

People tend to forget this, but there are ways to call for help without the need for electronics.

Flashlight or headlamp

Chances are you have some headlamps with you. You haven't? Then you should definitely pack them. I encountered so many situations where we planned to be back well before sunset but came back when it was already dark. Nothing serious need to happen. Maybe the group is slower than expected? Or the route was blocked and you had to make a detour? Point is, not having a (fully charged) headlamp with you can turn an unpleasant situation into a very dangerous one.

So you can use your flashlight to send out a distress signal.

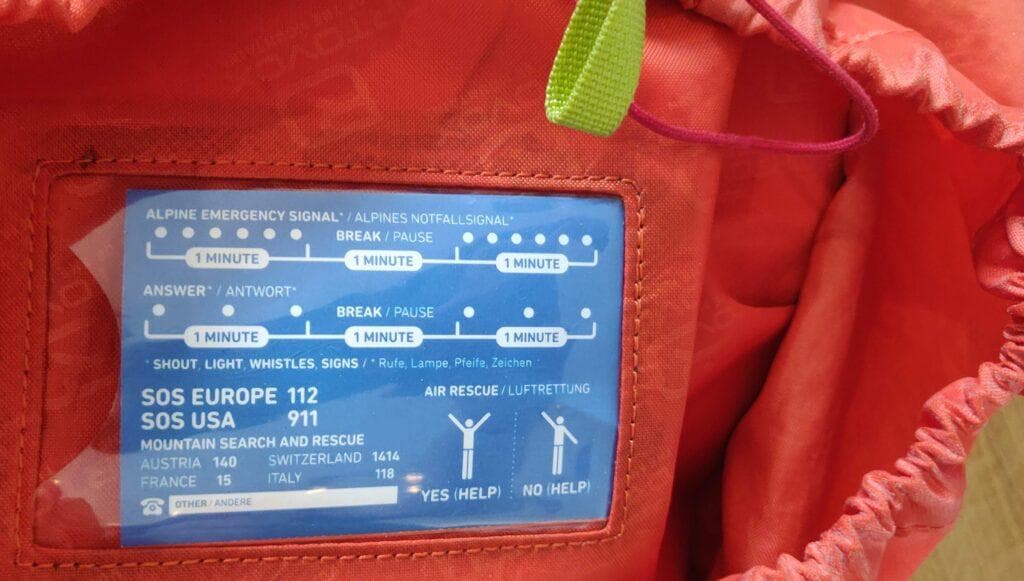

Alpine distress signal

If you are in an alpine area, you should use the alpine distress signal, which works as follows:

- Six flashes within a minute (every 10 seconds)

- 1-minute break

- Repeat

The proper response to this is:

- Three flashes within a minute (every 20 seconds)

- 1-minute break

- Repeat

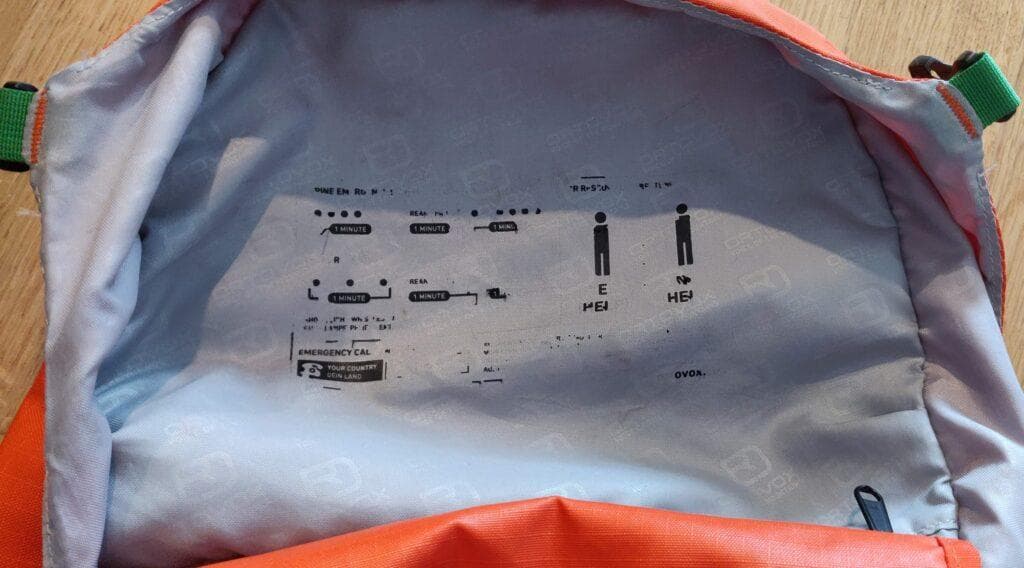

If you send this response it means that you received the signal and that you try to call (or come) for rescue. Difficult to remember? Fortunately, many backpacks have this information printed on the inside. Check it out. Just ensure the information is not as abraded as on mine.

A few tips on how to use the alpine distress signal properly

As the sender of the distress signal:

- Try different directions to make sure that you have a wide range of possible observers. A small hill with clear visibility in all directions helps.

- If you receive a response, don't stop sending the signal. You don't know what the responder would do next and whether he actually has the capability to rescue you. Keep sending the signal until rescue is with you.

As the receiver of the distress signal:

- Only send a response if you have the capability to help. If you are in an emergency yourself, it might be a good time to start sending the distress signal yourself.

- When sending the response, keep the timing slow enough (1 signal every 20 seconds). If you are too fast, your signal could be interpreted as a distress signal.

Fun fact: Did you know that the alpine distress signal was introduced as early as 1894?

SOS morse code

If you happen to be in a non-alpine area, you better use SOS morse code as the distress signal. Actually, you cannot only send an SOS signal, but you could use the full morse code alphabet to communicate proper sentences. Two-way! I very well remember these days in boy scouting when we learned the full morse code table by heart and started to send letters in-between tents. Those were times...

But no need to learn the whole morse code. The SOS signal will be sufficient for a start and it's easy to remember:

... --- ...

3 dots, 3 dashes, 3 dots. 3 short flashes, 3 long flashes, 3 short flashes. Repeat!

Whistle

If you have no line-of-sight to possible rescuers (or you really forgot your headlamp), you can use a whistle to signal an alpine distress signal or an SOS code. This could be helpful in poor visibility conditions (fog, whiteout) or in case of a crevasse fall.

Did you know that many backpacks already have integrated a whistle into the chest strap? Check your backpack or lookout for it when you buy a new one. Otherwise, dedicated storm whistles are available on the market.

How far can a storm whistle be heard? Estimation varies on this and it depends a lot on weather conditions, wind direction and on the actual whistle type. But an estimation between 0.5 and 1.5 miles (1-2 km) is a fair assumption.

Flares

Theoretically, you could take emergency flares on your trip. I have heard of people doing so but never actually seen or spoken to someone who does so.

Problems I see here is the additional weight plus the fact that someone would need to look exactly in your direction in the 60 seconds or so the flare burns down. So chances are your flare just burns down and no-one is going to rescue you. Compare this to the flashlight signal where you can send the signal all night long - or at least until the battery dies.

One possible application might be in case you were already able to call a helicopter (or rescue team) or someone else did because you haven't returned home safely. If the rescue team has difficulties to pinpoint your exact location, the flare might help to signal it.

Still a pretty rare scenario (and you could still use your flashlight to call the attention of the rescue team), so I would not really recommend to buy and carry these. Sad though, as I'm sure they are a whole lot of fun to trigger.

Use an emergency communication device to call for help

Chances are you don't want to rely on non-electronic communication only and you are looking at some kind of messaging device to call the rescue team. Let's have a look at the different types of emergency devices available today.

Cell phone / smartphone

I know what you think right now:

So this article is about how to call for help without cell service and now you recommend using a cell phone?

Ok, let me rephrase: "How to call for help if your mobile phone says it has no cell coverage?"

Fact is: Even if your phone says it has no signal, in many cases, it's still possible to issue a call to emergency services. There are two mains reasons why this works:

- On many networks, emergency calls receive a higher priority

- Emergency calls are allowed on any network, even if your phone is not registered on it. There might be no coverage for the network that your SIM card is registered for, but there could be coverage for another network.

You can just try to call 112 and your phone might switch to a different network automatically. The best tip I have heard though to leverage the second point is to call rescue as following:

- Verify that your phone has no coverage

- Switch it off

- Switch it on again

- When asked for the PIN code, enter 112 (Europe + international) or 911 (US) instead of the PIN. Your phone will automatically connect to the network with the strongest coverage.

If you happen to have a phone in your hand for which you don't know the PIN code (because it's not your phone, or you cannot remember the PIN in the heat of the moment), then probably the fastest method to trigger an SOS call is this:

Press and release power button 5 times in a row.

This should work on iPhones and Android smartphones unless disabled by the user. Depending on the software, a separate screen opens that allows you to trigger the call or it automatically triggers a countdown. If it's not working, you can still switch off and on as explained earlier.

Try sending a text message

Sending an SMS requires less network bandwidth than initiating a call. So even if you cannot get through with a call, you might be able to shoot out an emergency text message.

Not all rescue services will accept SMS though. So before heading out, check the website of the local/national emergency services and see whether they accept messages and where to send them. Otherwise, you need the fallback to alert your friends or family, hoping they would read the message early enough.

Traveling to Switzerland? I can highly recommend installing the REGA app. REGA is the main helicopter rescue service for Switzerland. The app will automatically take care of the network coverage, issuing an emergency call if possible or trying to send an text message which includes your GPS location in case the network coverage is not sufficient. Check the REGA website for more information and for download links.

Crucial: watch your battery level? Make sure your phone has enough battery. No trick above helps you if your battery dies before you can make the call. For longer trips, carry a power bank. And put your phone in flight mode. Especially in areas with bad coverage, searching and connecting for the best network constantly requires a lot of energy and drains your battery faster than normal.

Emergency radio

Emergency radios are small 2-way radio transceivers you can use calling for help via voice. You probably already know them as walkie-talkies.

Radios have to be set to a specific frequency. Everyone configured to this frequency can listen and speak on it, as long as they are in the range of your device. Most devices come with a selector of pre-configured frequencies (channels). Some more advanced devices give you the possibility to freely set the frequency within the range of the device.

The problems with radios:

- In case of an emergency, someone needs to listen on the specific frequency you are sending within your device's range. Unless pre-arranged before you leave for the trip, this is probably not the case.

- Radio frequencies are highly regulated in most countries. Buying a device for one country might not work if you travel and take it to another country.

Despite that, emergency radios could be helpful in two situations:

- You are going on a trip with multiple groups and you use the radios mainly for communication between these groups. In an emergency, you might not be able to directly call the rescue service but you might reach another group which could come for help or call for rescue if they have mobile coverage.

A variation of this is the expedition-style: You have someone at the basecamp who listens to the agreed frequency.

In both cases, you need to consider range limitations of your devices. - The local rescue service maintains and listens to an emergency frequency that you could use. For example this is the case in Switzerland where REGA maintains a network of antennas with national coverage and they listen on 161.300 MHz continuously. Products are available that are preconfigured for exactly this frequency.

I opted against buying such a radio device, mainly, because I wanted something that I can use internationally. But if you happen to travel the same area for all your adventures, this might be an option for you to look into. Just check beforehand, whether your local rescue service maintains such an emergency frequency.

Personal locator beacon (PLB)

Personal locator beacons are emergency devices which can send out a distress signal via a satellite network. Therefore they need a clear view of the sky. Originally they were mainly used in aviation and maritime, but now handheld devices for outdoor usage are also available.

Once triggered, the device sends a distress signal with its 406-MHz radio transmitter. This signal is received by the Cospas-Sarsat satellite system and routed to the mission control center (MCC) in which you registered your device. Once your alert is received by the MCC, they will organize rescue services based on the origin of your distress signal.

Register? MCC?

When you buy such a device, you have to register it with the MCC in your country. In most cases such registration is free and you also don't have to pay any monthly or annual subscription fee afterward. In that sense, the PLB is a great carry-and-forget device.

The main issue I see with these kinds of devices is that you cannot send any additional information with the distress signal. It's kind of all or nothing. Imagine this situation:

Hey guys. The weather is really turning bad and a storm is coming up. I will build a snow cave for the night. Can we check back tomorrow 5am and if there is no signal from my side you come for rescue?

How would you behave with a PLB when you cannot send such a message? Would you trigger an SOS right away, asking the rescue services to start some risky rescue operation in the storm? Would you wait until next morning, risking that you might not be able to issue the signal anymore?

In the end, this is a very personal decision. Do you need something for life-threatening situations only and you regard messaging capabilities as unnecessary? Then this might be a great device for you. You can find options in the range of 280 - 300 USD. Otherwise read on.

Satellite phone

Traditionally, satellite phones surely were the gold standard for remote communication. Satellite phones normally allow for voice calls to other devices of the same network, to landlines or mobile phones. Often they also include messaging capabilities, either device to device, via email or sometimes also via SMS to normal mobile networks.

You have to register with a satellite network and choose a subscription plan. For most plans you pay a register fee, a monthly or yearly fee and additional fees if you use more voice-time or messages than what is included in the subscription. Various satellite networks are available which differ in pricing, coverage and offered services.

If you need a proper communication device, not only for emergencies but for keeping in touch with friends and families, then this might be an option for you. If you're are just looking for an emergency device, this is probably an overkill. Usually, the devices are rather large and heavy, and the total costs for the device plus for the subscriptions can be quite substantial. Depending on the model, buying a sat phone can easily set you back 1000 USD - and that is not yet counting any subscription fees.

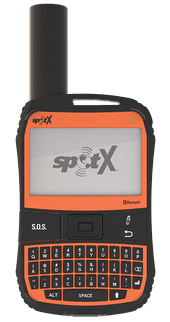

One-way satellite messenger

Trying to fill a niche for emergency messengers, one-way satellite messengers emerged. These are pocket-sized devices that use the same networks as satellite phones. They are smaller, lighter and less costly both in purchase price and subscription fees compared to satellite phones.

All products in this category include an SOS button. If you trigger it, a distress signal is sent to a rescue center (usually maintained by the satellite network operator) which in turn will relay the signal to the local rescue organization. In that sense, they are quite similar to a personal locator beacon (PLB). The main advantage over PLBs is that besides the SOS signal you can also configure custom messages which you can send to friends or family such as "I will return late, but no worries, I am ok.".

The best-known product in this category is the SPOT Gen3. As an emergency messenger, it has a few drawbacks, namely:

- You have to define the messages before you leave. So the messages have to be quite general and vague.

- There is no way to ask back if the receiver has difficulties to properly interpret the message.

That's why I would rather recommend a two-way satellite messenger than a one-way messenger. But if you are on a budget though, the one-way communication might be sufficient. You can find devices in the range of 150 USD.

Two-way satellite messenger

Let me spit it out directly: To me, two-way satellite messengers are the holy grail of emergency communication devices for the backcountry. They used to be similar in size and weight as satellite phones. But much innovation has happened in the last few years and now great and lightweight products are available.

How do they work?

As with one-way messenger, you can trigger an SOS signal. The main difference is that the rescue center can check back and ask for further clarifications. This can make a huge difference in the success of rescue services calling for the right resources and actually finding you.

You can also prepare custom messages or write specific message on the spot and send them to your friends and families. They can respond to your messages, either by replying directly to the message (email or text message) or via a web interface. Specifics depends on the device and operator network.

I believe, two-way satellite messengers cover everything that is needed from a true emergency communication device:

- Serves as a backup when you have no mobile coverage

- Work internationally

- Small and lightweight (at least nowadays)

- Allow for proper communication in both directions

Emergency device I personally use and love: Garmin inReach Mini

Earlier this year after doing all the research I decided to buy the Garmin inReach Mini. I have never used it for a true emergency (knock on wood), but for what I used it so far I'm very happy with it.

The inReach Mini is a two-way messenger with a small display and a few buttons (6 to be exact) but no full keyboard. Theoretically, you could type messages with these buttons but it will take ages. Normally you would connect your smartphone via Bluetooth and then you use your phone to read and send messages. If you have an emergency and your phone already died (which you should avoid by putting your phone in flight mode) you can still trigger an SOS, read messages and reply with the inReach Mini alone. It just takes you way more time to write the responses. One way around this is to use preconfigured text blocks. Some text blocks ship with the device but you can define your own.

The inReach Mini has an SOS button, mechanically well protected against accidental triggering (check the link at the end of article to learn why). If you push the button long enough, an SOS message is sent to the GEOS International Emergency Response Coordination Center located in Texas. Upon reception, they will ask back for further information and in parallel, they will coordinate with the rescue services at your current location. Do you wonder how this works in practice? Check out this wonderful article from Kristen Fuller on her personal experience:

https://www.outdoorproject.com/gear/sos-activating-scary-sos-button-my-garmin-inreach

Besides the SOS message you also have the ability to preconfigure 3 messages. Other than the text blocks, for the preconfigured messages you already define the full message and the recipient. Also, you can configure the exact GPS location to be automatically attached to the message. I have preconfigured the following messages on my device:

- Message #1: "Test message / Just testing whether my device is working properly."

Recipient: my own mobile phone number + email - Message #2: "Critical situation / We are in a critical situation, but not (or not yet) life-threatening. Assistance might be needed. Please get in contact to discuss."

Recipient: local rescue organization; they accept alerts via email and SMS - Message #3: "SOS Emergency situation / We have encountered an emergency situation, possibly life-threatening. Please send rescue support immediately."

Recipient: local rescue organization

Why I like this device so much: It's so small and lightweight, I forget that I actually carry it with me. I'm not even checking or pondering whether I would get into areas with no cell service. I simply pack it, every time. And that's how it performs the best: sitting there in the pocket of my backpack, doing nothing and giving me peace of mind that I can rely on it, in case I really need it.

Despite all the love, a few things to keep in mind:

- It's not cheap. I paid around 315 USD to buy it and I'm on a subscription plan that costs me another 20 USD per month (it's the freedom plan, so I can suspend the subscription every month if I don't plan to use it). However, for me, it's absolutely worth it.

- If you're new to satellite networks: it's not lightning speed like sending emails or texts. Satellite network messages need some time to get through. Depending on your location and surroundings, it can take 10-15 minutes for the message to deliver. If you don't have a clear view of the sky maybe longer.

- One critic I have is that the Garmin website and platform where you configure your device and messages could definitely use some facelift and modernization. I had some issues while configuring everything. But once it's done you won't use the website that often, so it's not a huge dealbreaker.

If you want a broader view and see some other products, check out the great reviews and comparison over at Outdoor Gear Lab. But be warned: they awarded the inReach Mini as their "Editors' choice", too.

https://www.outdoorgearlab.com/topics/camping-and-hiking/best-personal-locator-beacon

Independent of what you choose in the end, keep in mind: Have fun and stay safe!

One last thing: Curious to know what happens if you trigger an SOS accidentally but you don't notice? Read below well-written and gripping story from Dean Krakel. After that, you'll understand why Garmin decided to redesign the protection in front of the SOS button: A Colorado photographer thought he was alone in the Wyoming mountains. Then he heard a rescue helicopter.